How does a company like 23andMe link genetic markers to diseases?

March 21, 2017

- Related Topics:

- Consumer genetic testing,

- Genetic variation,

- Genomics,

- Personalized medicine,

- Bioinformatics

A curious student from California asks:

"I just got my results back from 23andMe and I was wondering how they link the genetic markers to the diseases, the ones where I have a predisposition for that disease.'

I think this is a question that a lot of people have after doing tests like 23andMe. These markers are just places in the DNA that in some studies were found in more people with a particular illness.

Most of these markers in the “health” section—especially with 23andMe health results in the past—are not for sure things. Sometimes, they aren’t even found in people with the illness that much more often than in people without the illness.

That’s why having one of these markers, let’s say for something like heart disease, increases your risk only a little bit. We also have to take into account that other factors—both genetic and environmental—play into who gets these conditions.

SNPs Aren’t Necessarily Bad

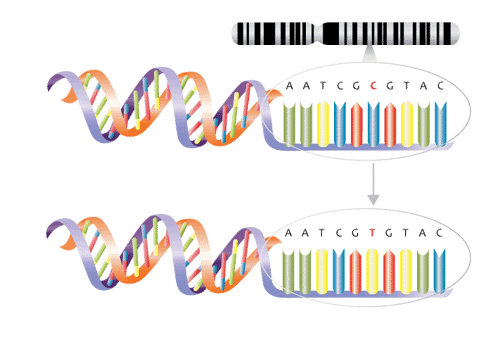

The genetic markers you’re talking about are called SNPs. This stands for “single nucleotide polymorphism.”

SNPs are just places in the DNA that can be different from person to person. Polymorphism actually just means “different forms.” That’s all a SNP is!

Imagine all of our DNA is a long sentence. SNPs are places in the DNA that can differ by just one letter, or in this case DNA base.

SNPs usually aren’t good or bad. In fact, they are the differences that make me different from you. Most of them don’t really hurt us or help us physically.

The type of SNP you’re asking about is one that has been linked to a disease. It’s important to remember that the SNP itself doesn’t cause the disease. Maybe something near the SNP plays a role in causing the disease, but it’s generally not the SNP itself.

Hunting for SNPs

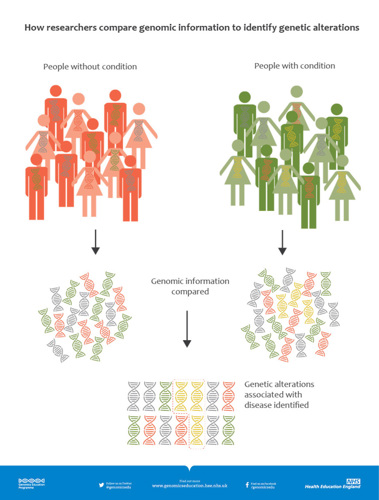

The way to link SNPs to diseases or other traits is called a genome-wide association study or GWAS. This kind of study does exactly what the name suggests. It lets scientists find places in our DNA (our genome) associated with specific traits.

Here is a great image that shows how this works:

This image shows two groups of people, one with the disease on the right and the other without the disease on the left. The yellow DNA is found more often in people with the disease and so it is a risk factor. Real life is often a bit messier than this.

For example, a certain rs3849942 SNP was associated with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) in a few studies. This means that people with this SNP were more likely to have ALS than people who didn’t have this SNP.

How do we know this? This type of study spits out what’s called an odds ratio.

This tells us the odds or chance of something happening given a certain condition. Then, this is compared to the odds for that thing happening when that condition isn’t met. This comparison is the odds ratio.

The odds ratio is a way to test whether or not two things are connected by more than just chance.

For ALS and this SNP, the odds ratio looks at how often people with rs3849942 (A;A) (the specific SNP) get ALS. Then we compare that to the number of people with the same SNP who don’t get ALS.

Notice that there are people who have rs3849942 (A;A) who don’t have ALS. So we can say that having this SNP definitely does not mean someone will get ALS 100% of the time! That’s why the overall risk of someone who has this SNP having ALS is so low.

An odds ratio will be equal to 1 if there is no connection between the SNP to the trait or genetic condition. In other words, if the same percent of people in the two groups have the SNP.

An odds ratio greater than 1 means that having the SNP makes someone more likely to have the condition. It was found more often in the ALS group. We would consider that SNP a risk factor for that condition.

An odds ratio less than 1 means having the SNP makes someone less likely to have the condition. This would make the SNP a protective factor for that condition.

The larger the odds ratio, the better the SNP is at predicting if someone will have the disease. Usually if the odds ratio is close to 1 (i.e. 1.2), then the SNP isn’t very good at predicting the condition. It is associated with the condition, but not strongly associated.

The GWAS research that has been done on the rs3849942 (A;A) shows odds ratios around 1.2-1.39 for ALS. This means that yes, the SNP is associated with ALS.

However, these numbers aren’t too much higher than 1. This tells us there were plenty of people in the studies who have this SNP but didn’t have the disease.

How do we interpret the GWAS results?

If most people who had that SNP had the disease, we’d see a much higher odds ratio. Scientists consider an odds ratio of 3 or greater to be significant.

One of the strongest SNP-disease links that scientists have found is for Alzheimer’s disease. This SNP is in a gene called APOE. The SNP that is linked to Alzheimer’s has an odds ratio of about 3.

It’s much higher than the 1.2 we have for ALS. However, we still see lots and lots of people with the higher risk flavor of the SNP who don’t get Alzheimer’s. We just expect to see more people with this SNP who get Alzheimer’s than people with rs3849942 who get ALS.

Lots of Limitations

Odds ratios like the one above for rs3849942 and ALS tell us that this SNP probably isn’t the best predictor of ALS. In fact, one might even ask if it is a SNP worth knowing: it only increases someone’s risk by a small amount. It could also cause someone to worry about getting the disease in the future.

The small odds ratio makes sense with what we know about the causes of ALS. Most cases aren’t inherited from our families.

A lot of diseases studied through GWASes are what we call multifactorial conditions. This means that genetic and environmental causes work together to determine who will get that condition.

Many of the health conditions on the old 23andMe reports (or if you used software to analyze your raw data) where you get a risk score (versus a carrier status result) are multifactorial conditions. Diabetes and lung cancer are examples of multifactorial conditions.

Because there are so many things influencing who gets the disease, one single SNP usually doesn’t play a big role on its own. That’s why your risk goes up if you have one of these SNPs. But it doesn’t go up by a ton. And you may have other unknown SNPs that lower your risk!

In contrast, there are some very, very rare genetic changes, or mutations, for early-onset ALS or Alzheimer’s disease. Having one of these changes could cause someone’s risk of getting one of these diseases to go up to 100%. Again, this is very, very rare, and is in no way linked to the risk SNPs we’ve been talking about!

Most cases of these conditions, like ALS or Alzheimer’s disease, are random because there are so many things contributing to whether or not someone gets the disease. When a disease seems to happen by chance, scientists call the condition sporadic.

So an odds ratio close to 1 tells us that there are probably a lot of other causes for those conditions that aren’t genetic. For instance, some other risk factors for Alzheimer’s disease are older age, having a family history of Alzheimer’s, experiencing head trauma, and having heart disease risk factors, like high blood pressure, high cholesterol, or diabetes.

In theory, one of these environmental exposures could have more influence on whether someone gets Alzheimer’s than their APOE SNP status.

We also have to keep in mind the ethnicity of the people in the GWAS. If the study was done on let’s say Swedish people, the results may not hold up in other populations, like Chinese or Hispanic individuals.

This matters when we’re interpreting your 23andMe results. If you’re Hispanic and all of the data supporting a connection between a SNP and a disease comes from studies in Swedish people, then it might not be applicable to you.

That’s the trick to understanding results like these: you really have to think through each one. There are so many factors that change your risk for whether or not you will get a condition.

It’s important to remember that a risk SNP is only one of these factors. There are plenty of people with these SNPs who are perfectly healthy throughout their lives, and vice versa, there are people without these SNPs who get the disease.

A large role is up to chance and out of our hands. But by controlling our other risk factors, we can decrease our chance for disease.

Author: Karina Liker

When this answer was published in 2017, Karina was a student in the Stanford MS Program in Human Genetics and Genetic Counseling. Karina wrote this answer while participating in the Stanford at The Tech program.

Skip Navigation

Skip Navigation