Is your dominant hand something you’re born with or something you develop?

July 16, 2019

- Related Topics:

- Complex traits,

- Environmental influence,

- Developmental biology,

- Handedness

A curious adult from Alberta asks:

"Is your dominant hand something you’re born with or something you develop? I’ve always said I’m left handed because I write with my left hand. But I use my right hand for other things. When does one say they’re ambidextrous? I thought to be ambidextrous you had to be able to do tasks equally well with both hands."

Being ambidextrous usually means that you can use both hands equally well. Being mix-handed means that you prefer different hands for different tasks. Very few people are either ambidextrous or mix-handed: most people have a preference for one hand.

Approximately 10% of people are left-handed, 1% is ambidextrous or mix-handed, and the rest are right-handed.1

However, a left-handed person may be more likely to be able to do tasks with their right hand, than vice versa.

How our environments can affect our behavior

Some of those reasons would be environmental. Since more people in the world are right-handed, our environment is often set up to favor working with your right hand.

Think about using a pair of scissors. A lot of scissors are right handed: a right hand fits better through them. Or in a restaurant, the glass is usually placed at the right side of the plate.

These little things happen over and over again. This can help to train a left-handed person’s right side to be good at doing these things.

However, a right-handed person is less likely to have to use their left hand. Very few places have left-handed scissors only, and fewer waiters place a glass by your left side.

These environmental factors might make someone prefer their right or left side for certain activities. Traits like this, which can be changed by training or other environmental effects, are called plastic traits.

The genetics of handedness

What about the genetics of handedness? Is it more likely to be passed on through our DNA?

Most scientists agree that there is some degree of genetics in handedness. For example, there has been a study calculating that about 25% of this trait can be explained by genetics.2

However, scientists also agree that the genetics of handedness is complicated. Identical twins will not always have the same preference for hands, for example. And researchers have had not much success in finding genes that explain handedness.3,4

Biology: why most people prefer their right hand

Going further — what is the biology behind handedness? Why are people more likely to be right-handed in the first place?

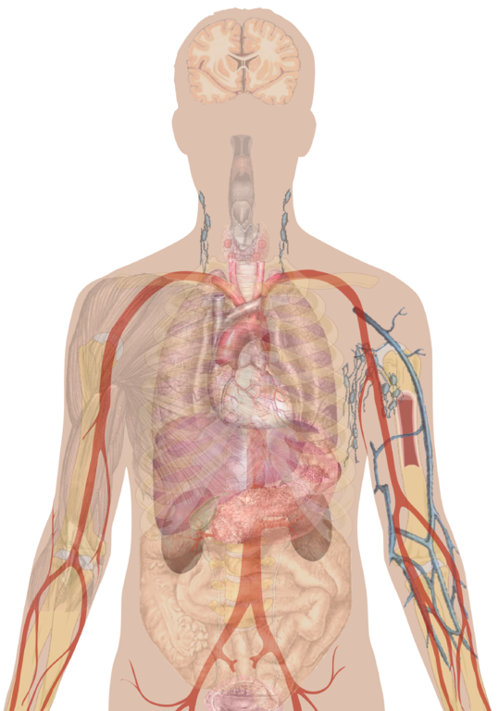

Our bodies are actually not made symmetrically! Even though it looks like we are the same on the right and left sides, there are a lot of differences. Notice on the right how a human’s organs aren’t symmetrical.

This is called left-right asymmetry, and it’s established early on in the development of the embryo.

Some scientists think that handedness begins to be established before birth, from recordings of fetuses moving their arms in the womb.2,3 Indeed, one gene that has been found to be associated with handedness also affects other aspects of right-left asymmetry.4

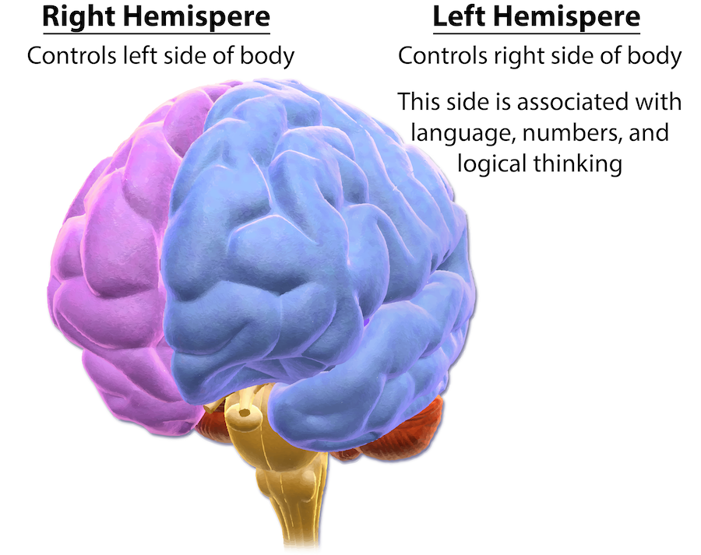

Our brains are asymmetric too! The left side of the brain is thought to contribute more to language, logic, and number skills.5 And weirdly enough, the left side of the brain controls the right side of the body. (And the right brain controls the left body.)

Since the left hemisphere is associated with language and details, that could be a reason why it is more likely to control the dominant hand: writing is a language and detail-oriented task.

But that is just speculation at this point—more research needs to be done to explain why humans tend to prefer their right hand, and why some people prefer their left hand!

Author: Kei Yamaya

When this answer was published in 2019, Kei was a Ph.D. candidate in the Department of Developmental Biology, studying meiotic chromosomes in c. elegans in Anne Villeneuve’s laboratory. She wrote this answer while participating in the Stanford at The Tech program.

Skip Navigation

Skip Navigation