Do you think we’ll ever bring back dinosaurs or mammoths? And should we?

March 20, 2013

- Related Topics:

- Bioethics,

- Genetic engineering,

- Futuristic science,

- Ancient DNA

An undergraduate student from the Philippines asks:

These are two very different questions. Yes, we’ll probably be able to bring back mammoths one day. It won’t be easy but probably doable. Dinosaurs are much more of a stretch.

None of these are going to be tomorrow though. Same thing with Neanderthals, the Dodo bird or the Saber Tooth Tiger. As we’ll see in a bit, we just don’t have the technology yet to bring these guys back.

Now I don’t want you to come away thinking bringing back extinct species is all science fiction, far off in the future stuff. It isn’t. This is an active area of research, called de-extinction. And there are a few species that we could bring back right now with our current technology.

One famous case is the Pyrenean Ibex. The last one of these wild goats died in 2000. But luckily for this species, scientists saved a sample of cells from this last living Ibex. These cells are probably enough to resurrect this Ibex right now (or at least in the very near future).

And this Ibex actually was cloned and brought back to life in 2009. But the baby goat only lived for seven minutes, and died due to breathing problems. That means that the Pyrenean Ibex is perhaps the only species that has gone extinct twice.

So far scientists haven’t been able to clone the Ibex successfully, but the problems are more on the order of technical glitches as opposed to major technical hurdles. If we want to, we probably could bring this species back from the dead.

To de-extinct, or not to de-extinct

Of course the new question then is whether we should bring the Ibex or any species back. A case can probably be made for the Ibex since we wiped them out just a few short years ago and we have the technology right now to do it. The same argument might be made for the Tasmanian Tiger or the Quagga too.

But it is much less obvious whether we should bring back dinosaurs, mammoths or Neanderthals. There isn’t really any good reason to bring any of these back except to study them (and maybe to prove we can). And there are probably plenty of reasons not to.

There isn’t an infinite amount of money to put into conservation. Any money that goes to bringing a mammoth back might be taken away from people trying to keep elephants from going extinct. If that’s the trade off, the mammoth should probably stay extinct.

Another problem is the effect that long lost animals might have on our current environment. For example, imagine how many species would get wiped out if a dinosaur got loose. Is bringing back a dinosaur worth killing off a bunch of current species?

We also need to think about how having this tool available to us will affect how we think about life on the planet now. Some people predict that the human population will peak at about 9 billion or so but then could fall off pretty dramatically. This means that there will be more space for wildlife in the future than there is now.

If we can resurrect lost species, we might decide to save some cells from endangered animals and then let the animals die off. Then, when we have more space because our population has gone down, we will bring these species back. This will take the steam out of the conservation movement and who knows what will become of our environment. And whether we will be able to reconstruct the environments we let die.

Another reason to think long and hard about this is the welfare of the animal (or the Neanderthal, which is human!). The technical glitches I talked about are things like spontaneous abortions, still births, deformities and so on. Getting the conditions right will mean a lot of pain and suffering for animals and their surrogate mothers. We have to decide if bringing back a species is worth the suffering of a lot of individuals.

The final big reason to think twice about bringing back species is that what we bring back might not be the same as what was there before. We may go through all the work, put all those animals through the pain and what we get out doesn’t act like the old species did. Heck, it might not even look exactly like the old species!

It will have the same DNA, but it might not be the same beast. We are more than our DNA … we are also how our DNA gets used. This is where the environment including the womb we develop in, the food we eat, where and how we grow up and so on can change who we become.

So in the end we could recreate a mammoth that doesn’t act like a mammoth did. Of course, there is no way we could know. We will have an animal running around with mammoth DNA in its cells, but we won’t know if it is really mammoth-like at all.

For all these reasons, the head says don’t revive extinct species. And yet the heart is drawn to the coolness of bringing back a dinosaur or a mammoth. Just think how many kids we could get to go into science if we had living dinosaurs running around.

At least we don’t have to actually make the decision right now on whether to clone most of these animals or not. We simply don’t have the technology to resurrect most species. Not yet anyway …

Cloning 101: start with good-quality DNA

DNA has the instructions for making a living thing. Unfortunately the DNA we can make in a lab can’t be read by a cell. So even if we could make a complete set of mammoth DNA, we can’t yet get it to become a mammoth.

A big reason for this is packaging. Humans have six feet (two meters) of DNA crammed into the nucleus of a cell. This nucleus has a diameter of about six micrometers. To give some perspective, if the period at the end of this sentence were a nucleus, we’d need to fit one kilometer or over 1,100 yards of DNA in it (assuming the period is three millimeters in diameter).

To pull this off, the DNA has to be packaged just so. It has to be “rolled” onto little spools called histones that then get spooled into larger structures that again get spooled and folded and so on. Right now, only a cell can pull off this intricate origami. Scientists cannot yet do this in the lab.

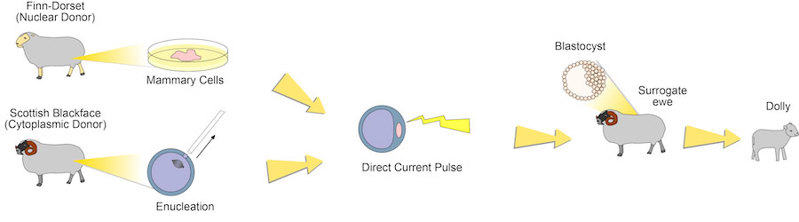

This is why any cloning done right now is done with an intact nucleus where the DNA is already packaged for us. As you can see from the picture below, scientists use a cell’s nucleus and not just its DNA to make a clone.

First scientists remove the nucleus from an egg. Then they replace it with a nucleus from the animal they want to clone. The egg is then treated so the DNA goes back to being embryonic DNA and placed in a surrogate mother where it develops and grows. Eventually, if everything goes well, the clone is born.

This was possible with the Ibex because intact nuclei were saved from the last living member of the species. But as I mentioned, we haven’t managed to pull it off just yet. The best we’ve done is an Ibex that died soon after birth. Still, we’ll get there with a little tinkering if we really want to.

The mammoth is a different story. We might be able to find an intact nucleus, since there are mammoths that have stayed frozen for thousands of years. But so far this hasn’t happened.

If we can’t rescue an intact nucleus or a working sperm cell, we’ll have to make mammoth DNA in the lab (which will be tricky on its own). This means that before we can clone a mammoth, we’ll have to learn how to get a cell to fold our DNA into the right shape or learn to fold it ourselves. This won’t happen soon.

Dinosaurs are even a longer shot. Before we can make DNA in a lab, we have to know what to make! And it’s really unlikely that we’ll ever find intact dinosaur DNA. It’s just too long ago, and DNA breaks down over time.

Our best bet to make dinosaurs may be to reverse the process of evolution and turn birds into dinosaurs. And honestly, how satisfied would you really be with a chicken that looks sort of like a T-Rex? And you thought mammoths were a long shot!

Author: Dr. D. Barry Starr

Barry served as The Tech Geneticist from 2002-2018. He founded Ask-a-Geneticist, answered thousands of questions submitted by people from all around the world, and oversaw and edited all articles published during his tenure. AAG is part of the Stanford at The Tech program, which brings Stanford scientists to The Tech to answer questions for this site, as well as to run science activities with visitors at The Tech Interactive in downtown San Jose.

Skip Navigation

Skip Navigation