Are hormone responses controlled completely by our genetics?

July 26, 2022

- Related Topics:

- Environmental influence,

- Complex traits

Azad from Iran asks:

“Is hormonal responses in our body are completely relying on genes or not?”

This question is a common theme in biology: how much do genes determine a trait, versus other factors in the environment? This is something geneticists think about a lot. And the short answer is that both genetic and environmental factors play major roles.

Hormones in the body are complicated. Hormones help guide body development and puberty, allow different parts of the body to communicate with each other, and influence day-to-day events like sleep cycle.

Your genes do influence your hormones. But hormones are also an important system that helps our bodies respond to signals from the environment. And that means they’re affected by those environmental signals.

Our genes play a big role

Genes play an important role in this system. And it turns out there are a lot of genes involved in hormone responses.

For example, the Growth Hormone 1 (GH1) gene has the recipe for growth hormone. If someone has a mutation in this gene, they may not be able to make the correct amount of growth hormone. This can cause that person to be shorter than typical.

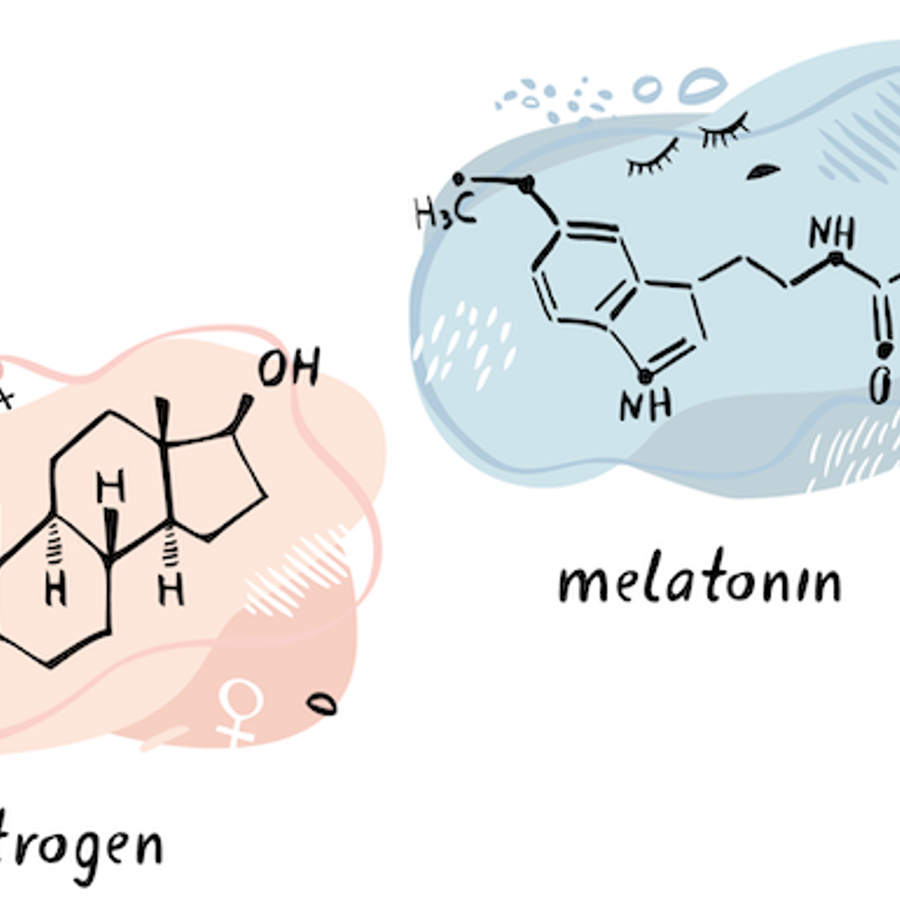

Other genes contain instructions to help the body detect and recognize the message that hormones are sending. The growth hormone receptor detects and responds specifically to growth hormone. If someone has a mutation in their Growth Hormone Receptor (GHR) gene, their body can’t sense that hormone correctly. They would be shorter than typical … even if their body made plenty of the growth hormone!

But those aren’t the only types of genes that matter. GH1 and GHR are part of a larger network of genes that affect your growth.

When growth hormone’s message is received by its receptor, this signals the cell to turn on an entirely different gene: insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1). This is what actually causes us to grow. If someone has a mutation in their IGF1 gene, their body can sense growth hormone, but it still can’t respond to it. Even though they’re making enough growth hormone and sensing it, they would still be shorter than typical.

But it gets more complicated. The Growth Hormone Releasing Hormone (GHRH) gene makes a hormone that tells the body when to release growth hormone! Genes like this are important because hormones have such huge effects on the body that we only want them turned on at the right times.

At least 19 genes play a role in making, sensing, and controlling growth hormone.1 That sounds like a lot, but actually, the growth hormone pathway is simple compared to some other hormones. For example, over 80 genes play a role in making, sensing, and regulating estrogen!1

It’s easy to see how genes affect hormones. This isn’t the full story though…

Our environment plays a bigger role

While genetics matter, environmental factors actually play the biggest role in shaping day-to-day hormone responses. In fact, our hormonal responses are largely guided by cues from our environment.

Food provides us with the energy and building blocks our bodies need in order to function and grow. When we aren’t eating enough food, our bodies make sure that the limited energy is used to keep our bodies functioning. Growth becomes less important. When that happens, the body will stop responding to growth hormone and growth will stop until enough food is eaten.

Food isn’t the only external factor that can affect hormones. Melatonin is a hormone involved in our sleep-wake cycle. When it gets dark at night, your body produces lots of melatonin. This causes some changes in brain activity that help us to fall asleep. Then when we’re exposed to light, levels of melatonin decrease, so we feel less sleepy and more awake.

Originally, melatonin levels would have increased after sunset and then decreased at sunrise, creating a consistent sleep cycle. But now we have lightbulbs that keep our environment brightly lit well after sunset. More and more scientists have started investigating whether this impacts melatonin levels and sleep quality. And while a lot of work still has to be done, studies do suggest that exposure to light at night can delay when melatonin increases, which may shift our sleep-wake patterns.2

These are just a couple of the many non-genetic factors that impact our hormonal responses. Aging, diet, stress, sleep-deprivation, pregnancy, immune responses, and medications can all cause levels of certain hormones to go up or down.

But wait, there’s more!

Hormones can turn genes on and off

Earlier I mentioned that growth hormone causes a different gene to turn on: IGF1. And this is pretty common. Genes can affect hormones, but hormones also affect genes!

One famous example of this is estrogen. Estrogen affects the expression of hundreds — maybe even thousands! — of genes. These genes have many different functions, playing roles in bones, heart function, cancer, etc. Because of this, when estrogen is given to someone as part of hormone therapy, it can have a really wide range of effects.

Another example is cortisol. Cortisol is often thought of as the “stress hormone” since high levels of cortisol are released when we are stressed. The receptor that recognizes cortisol is found on lots of different types of cells all throughout the body. When this receptor is activated, it changes the expression of thousands of genes — an estimated 10-20% of our genome!3 These genes affect immune responses, metabolism, growth, and many more processes based on what type of cell is expressing them.

In the end, hormone responses are really complicated! Genes, environmental factors, and even other hormones can all play an important role in controlling a hormone.

Author: Ruth Schade

When this answer was published in 2022, Ruth was a Ph.D. candidate in the Department of Microbiology & Immunology, studying what makes some macrophages more permissive for intracellular Typhoid replication than others in Denise Monack’s laboratory. She wrote this answer while participating in the Stanford at The Tech program.

Skip Navigation

Skip Navigation