Why do people with only one X chromosome have symptoms, if only one would be active anyway?

November 1, 2017

- Related Topics:

- Chromosomes,

- Trisomy/Aneuploidy,

- X inactivation,

- Genetic conditions

A curious adult from Saudi Arabia asks:

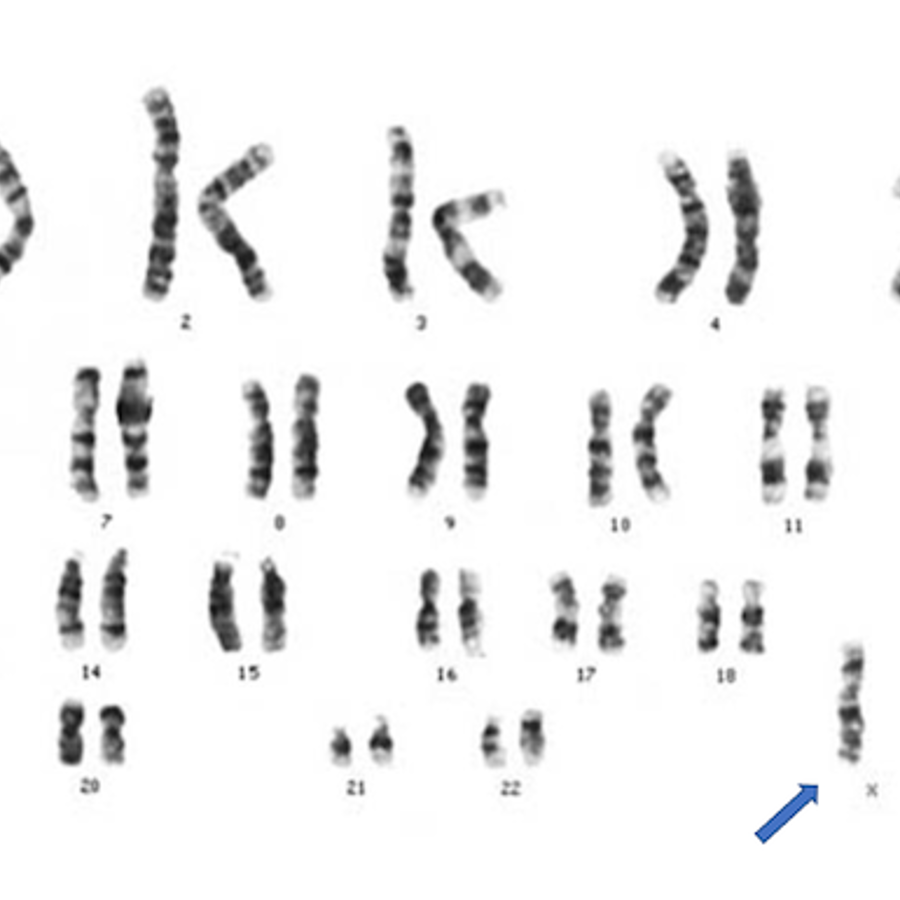

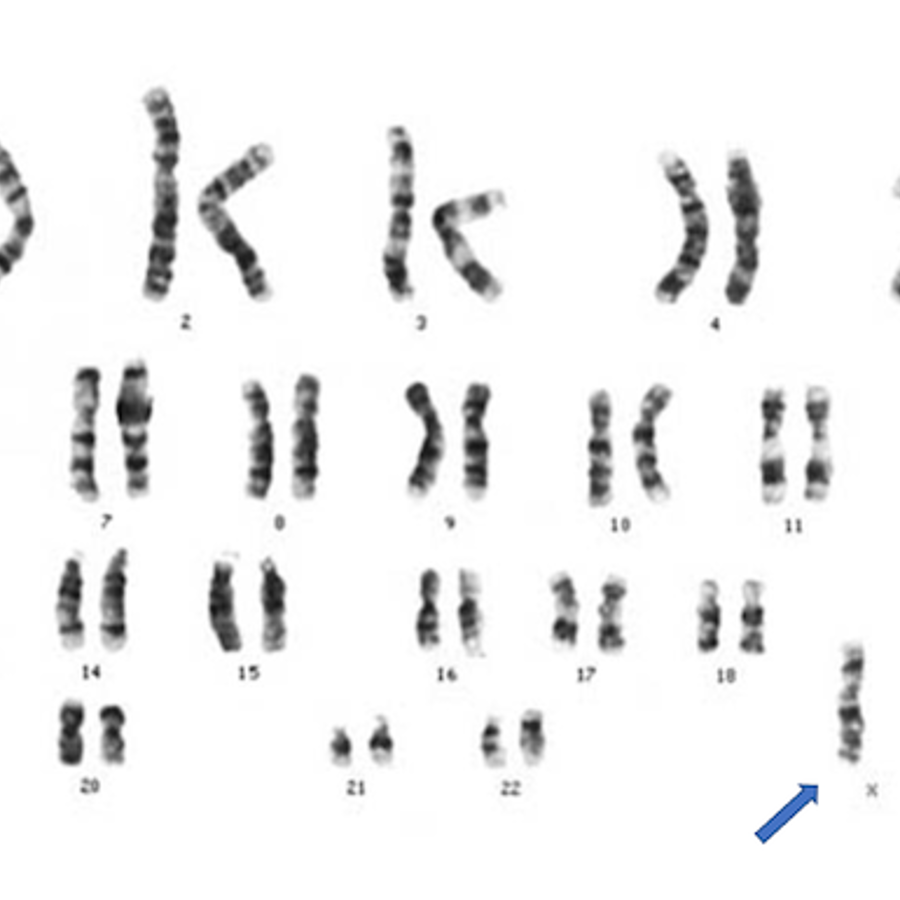

"Women with Turner syndrome have just one X chromosome but women usually only have one working X because of X-inactivation. Why do women with one X chromosome have any symptoms?"

It is true that in people with two X chromosomes, one of those X chromosomes is inactivated. But the key is that it is not completely shut off. Some of that second X is still turned on.

This is why people with Turner syndrome, who have a single X chromosome, have symptoms. They are missing that small part of the inactivated X that escapes the inactivation.

Well, more than a small part.

In people at least, something like 15% of the inactivated X is still doing its job. That is different than in, say, mice, where only around 3% is working.

So this explains why people with Turner syndrome have symptoms. And it also explains why some people who have three X chromosomes (triple X syndrome), can have symptoms too.

People with triple X have one completely working X and two copies of the mostly inactivated X. This extra bit of working X doesn’t always cause symptoms but it can.

The bottom line then is that an inactivated X is not completely inactivated. And just to keep things interesting, it turns out that some of the parts of the X that keep working are found on the Y chromosome too!

X-inactivation is more complicated than we learn about in school. Which of course makes it so much fun.

15% of Genes Still Working

Your DNA has the instructions for making and running you. These instructions are stored in 23 long stretches of DNA called chromosomes. The X is one of these chromosomes.

Most chromosomes come in pairs. So you have two copies of chromosome 1, two copies of chromosome 2, and so on.

Sex chromosomes are a bit different. They come in either X or Y. Generally, people with a Y chromosome are born male. Most men have one X chromosome and one Y chromosome (XY).

People without a Y chromosome are usually born female. That includes anyone who has entirely X chromosomes — whether they have one, two, three, or more of them!

A big part of the instructions in your DNA is found in genes. Each gene has the instructions for one small part of you. The X has around 800 out of the 20,000-25,000 human genes.

Since most chromosomes come in pairs, we have two copies of most of our genes too. And many genes are set up to work best with two copies.

When a gene can’t work well as a single copy, scientists have given it the name haploinsufficiency. I promise to not use that word again…it is just good to have the scientific word in case you want to do some more research.

Because around half of humanity, the males, have just one X, most of the genes on the X have evolved to work as a single copy. But as I said, not all of them have.

Over 100 of the genes on the X chromosome work best as pairs. Scientists refer to these as “escape genes” because they escape inactivation.

There can’t be a more exact number because different women have slightly different numbers of genes that keep working. There is a bit of wiggle room in the number of genes shut off on the inactivated X.

When One Isn’t Enough

One way to think about yourself is a chocolate chip cookie. (Bear with me here.)

Each gene is like one small part of the recipe. Add two cups of flour. Add two eggs. And so on.

In the end, if you have the right number of ingredients and add them at the right time, you end up with chocolate chip cookies. And if you have the right number of genes that get turned on and off in the right way, you end up as a person without symptoms.

Like any analogy this one is not perfect. To get at why you sometimes need two copies of a gene, we need to tweak things a bit.

Instead of, for example, saying, “Add two cups of flour,” to be more like a gene we want to say “Add one cup of flour” twice:

- Add one cup of flour

- Add one cup of flour

Losing one of these means you get half as much flour and so the cookies are not the same. They are still cookies but they have a set of symptoms — they are “flat, brown and crispy.”

This is sort of what happens with a lot of our genes. To get the right amount of “flour” we need both sets of instructions.

But this isn’t true of every part of the recipe. If we add half the chips they aren’t that different. Heck, some people like a little less chocolate in their chocolate chip cookies.

Same thing with our genes. Many, many of our genes work perfectly fine with just one copy. But not all of them.

Now of course our genes aren’t really recipe instructions. Instead they are the instructions for making tiny molecular machines called proteins that do work in our cells. Or give those cells structural support. Or pretty much anything else about building, running, and maintaining a cell.

For many of our genes, we need two copies so we get enough protein made. Otherwise, things can go wrong (like our cookies with too little flour).

The SHOX Gene

The gene that has been linked pretty conclusively to some of the symptoms of Turner syndrome is the SHOX gene. It has the instructions for a protein that is important in the development of the skeleton, especially the arms and legs.

The SHOX gene is found on both the X and the Y chromosome. This means that both biological males and biological females usually have two copies of this gene.

Women with Turner syndrome who have a single X have just one copy of this gene. Scientists think that their short stature, an average height of 4 foot 7 inches, is partly due to the loss of this extra copy of the SHOX gene. Other symptoms can also be tied to having just one copy of this gene.

Scientists are looking for other genes that might explain the symptoms seen in Turner syndrome.

Author: Dr. D. Barry Starr

Barry served as The Tech Geneticist from 2002-2018. He founded Ask-a-Geneticist, answered thousands of questions submitted by people from all around the world, and oversaw and edited all articles published during his tenure. AAG is part of the Stanford at The Tech program, which brings Stanford scientists to The Tech to answer questions for this site, as well as to run science activities with visitors at The Tech Interactive in downtown San Jose.

Skip Navigation

Skip Navigation