What are the chances my husband carries Kabuki syndrome? He has an affected nephew.

February 17, 2017

- Related Topics:

- Genetic conditions,

- Mutation,

- Autosomal dominant inheritance,

- X linked inheritance,

- Carrier

A graduate student from the UK asks:

“My sister in law has 4 kids with the last one having the genetic disorder Kabuki Syndrome. I have read that if the kid is a boy, the syndrome is carried by the mother, who in this case is my husband’s sister.

What is the probability of my husband carrying it? When is the best testing for it? Should we test him before a future pregnancy or the fetus once pregnant?”

Odds are that your husband isn’t a carrier for Kabuki syndrome because of how it is passed on. It tends to follow one of three patterns, and from the info you provided he probably isn’t at risk.

The most common way for people to end up with Kabuki syndrome is that it literally appears out of nowhere. Basically, the person’s DNA ends up with a new mistake in it that did not come from either parent. This kind of new mistake is called a de novo mutation.

If this is the case, then most likely your nephew’s Kabuki syndrome is unique to him. He could pass it on but it did not come from one of his parents.

There are two other ways it is passed down. In these dominant conditions, the only way to get the disease is if one or both parents have it too.

Since your husband does not have Kabuki syndrome, he almost certainly can’t pass it on. This is not how the disease usually works.

So a genetic test wouldn’t really be all that helpful in this case.

However! Sometimes people with Kabuki syndrome can have mild symptoms that aren’t noticed right away by a doctor. Having your husband talk to his primary care doctor about the family history could be a good place to start.

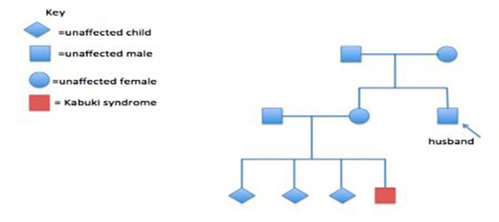

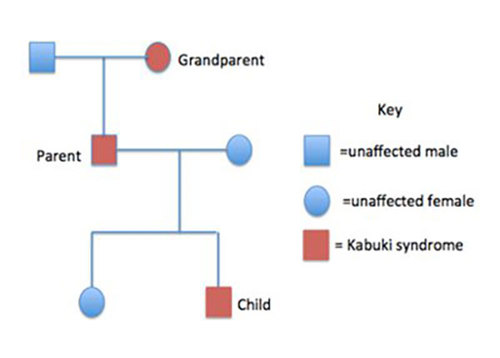

Here is the family tree you might get from such a discussion:

Squares are males, circles are females. Red means that the individual has Kabuki syndrome.

Each horizontal line represents a different generation (child generation, parent generation, and grandparent generation). We can lump people together in a generation if they were born and live at about the same time.

As you can see, the only case is your nephew.

So the bottom line is this: unless your sister-in-law and your husband show mild symptoms of Kabuki syndrome, odds are that your husband cannot pass Kabuki syndrome down to your kids. Your nephew (in red) would be the only individual in your family with Kabuki syndrome.

Most People Do Not Inherit Kabuki Syndrome

Kabuki syndrome is pretty rare. Only something like 1 in 32,000 newborns are born with it each year.

People with this condition can have a wide variety of symptoms in many parts of the body. They often have arched eyebrows or larger ears. Some will also have trouble with thinking and understanding, so special education can be helpful. Click here to learn more about the symptoms associated with this condition.

Problems in two different genes are known to cause Kabuki syndrome. These genes are called KMT2D and KDM6A.

Genes are the individual instructions within our DNA that give us certain traits. For example, we have genes for hair color or eye color. KMT2D and KDM6A are genes that have the instructions for doing important things in our bodies.

Genetic conditions, like Kabuki syndrome, can be caused by mistakes or problems in the spelling of these genes. These spelling mistakes are called mutations.

As I said before, mutations in these genes aren’t often passed down. Instead, they simply appear in the DNA of the family member.

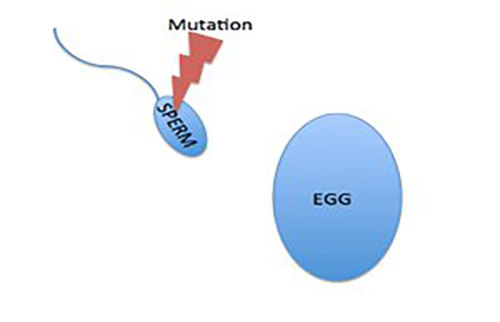

This happens because our instructions are not as stable as you might think. Certain things in the environment like UV light from the sun can damage it and cause mistakes. And just like we make mistakes, our cells sometimes do too when they copy their DNA.

These aren’t common but they do happen. And when they happen in the KMT2D and/or KDM6A gene, then the end result can be Kabuki syndrome.

This can happen to sperm or egg before fertilization:

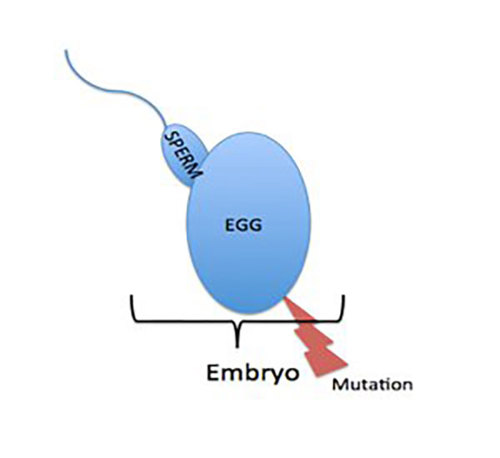

Or right after fertilization has happened:

Either way, the baby would have a difference in their DNA that mom or dad did not have.

Either way, the baby would have a difference in their DNA that mom or dad did not have.

In rare cases, however, the mutation can be passed down from parent to child. Since these genes are passed down differently, I will deal with each individually. Keep in mind, though, that with either, a parent has to have it to pass on to his or her kids.

In other words, there are no carriers with either. You can’t have a hidden copy of the nonworking gene. You either have the disease or you don’t.

As I said above, there are cases where a parent might have a very mild case of Kabuki syndrome and not know it. In this case, he or she could pass it down to the child even though they might think they do not have it.

Autosomal Dominant Kabuki syndrome

Mutations in the KMT2D gene cause around 75% of Kabuki syndrome cases that have symptoms. So this is the most common cause.

Like the majority of our genes, most everyone has two copies of KMT2D. We get one copy from mom and one copy from dad.

There only needs to be a problem or mutation in one copy of the KMT2D gene to cause Kabuki syndrome. This is called autosomal dominant inheritance.

So in this case, a child could inherit a mutation in KMT2D from either parent. However, this would mean that one of the child’s parents would also have Kabuki syndrome.

But like I said before, it isn’t quite this simple. Sometimes the parent may have mild symptoms and may not have a diagnosis.

Here is what a family tree might look like if it were passed down:

As you can see here, it was passed to each generation. But it doesn’t have to be this way.

If a parent has Kabuki syndrome, each child has a 50/50 chance to inherit the copy of the gene with a harmful mutation. 50/50 because the parent could either pass the copy of the gene without the mutation or the copy of the gene with the mutation. Which gets passed is random chance, it’s like a flip of a coin.

Unless your husband shows any signs of Kabuki syndrome, odds are he does not have the same mutated gene as his nephew. Which means he can’t pass it down to your children.

X-Linked Kabuki syndrome

About 9% of cases of Kabuki syndrome are caused by mutations in KDM6A, inherited in an X-linked dominant manner. This means that this gene is located on the X-chromosome and like autosomal dominant inheritance, having only one mutated copy is enough to cause Kabuki syndrome.

X-linked diseases are a bit tricky because biological females have two X chromosomes and biological males have an X and a Y. When parents have a male son, he inherits the Y-chromosome from his father and the X-chromosome from his mother, like this:

If a boy has a mutation in a gene on his X-chromosome, there are two possibilities:

- He could have inherited it from his mother

- There was a de novo, or new, mutation.

For a daughter, she inherits one X-chromosome from her father and one from her mother.

If she has a mutation on an X-chromosome, she could have inherited it from either her mom or her dad OR it could be a new mutation in her and not come from either parent.

What I believe you’re referencing in your question is Kabuki syndrome being inherited in an X-linked fashion, from mother to son. However, if this was the case, your sister-in-law would most likely also show symptoms of Kabuki syndrome.

By looking at large groups of individuals with Kabuki syndrome, scientists have discovered that de novo mutations are common for mutations in this gene. In fact, there haven’t been any reports of more than one family member having Kabuki syndrome caused by mutations in KDM6A.

If this was the case for your nephew, then your sister-in-law would not be a carrier of Kabuki syndrome. If she’s not a carrier, then your husband is not at risk to be a carrier either.

Genetic Testing for Kabuki Syndrome

If your nephew had genetic testing, it may have told your family one of three things.

- That he has a mutation in KMT2D, causing autosomal dominant Kabuki syndrome. Your sister-in-law and her husband could also have genetic testing to confirm that they are not carriers for the same mutation in that gene.

- That he has a mutation in KDM6A, causing X-linked Kabuki syndrome. As we talked about, this would most likely be a de novo mutation since familial cases have not been reported, so testing other family members wouldn’t be needed.

- It did not find a genetic answer at this time. However, this doesn’t change his clinical diagnosis.

Genetic counselors are available to talk through testing options for couples with family histories of genetic conditions. Genetic testing can be done on a blood sample and it takes usually about 4 weeks to get results. The best time to determine genetic risk or carrier status is before pregnancy. However, once a mutation is identified in a family, testing during pregnancy is also available. You can find a genetic counselor in your area here.

Author: Danielle Dondanville

When this answer was published in 2017, Danielle was a student in the Stanford MS Program in Human Genetics and Genetic Counseling. Danielle wrote this answer while participating in the Stanford at The Tech program.

Skip Navigation

Skip Navigation