Why does Ancestry.com show that my sister, mother, and I have the same DNA breakdown?

November 18, 2016

- Related Topics:

- Ancestry,

- Ancestry tests,

- Consumer genetic testing

A curious adult from New York asks:

“I’ve heard that no one has the exact same DNA except for identical twins. But Ancestry.com DNA tests showed that my sister, mother, and I have the same DNA breakdown (100% Eastern European). My sister and I are not twins. What is the reason for this similarity? Should my other siblings take the test, too?”

You’re absolutely right! Since you and your siblings are not identical twins, you almost certainly don’t have the same exact DNA.

DNA tests like Ancestry.com, though, only look at some of your DNA to determine your ancestry. And they look at the parts of your DNA that are more likely to be the same between people from the same parts of the world.

So the fact that your parents and two of their kids all came back 100% Eastern European means the other siblings probably don’t need to be tested too. At least not for ancestry.

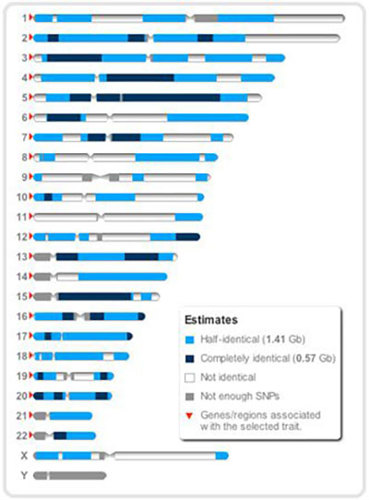

If you’re interested, there are different DNA tests that let you see the differences between you and your siblings. In fact, a site like GEDmatch can use your family’s raw DNA data from companies like Ancestry.com to do just that. They would all show you sharing around 50% of your DNA with each of them.

The bottom line, then, is that the results depend on what DNA a test looks at. To understand why, we need to take a step back and talk about why people from the same part of the globe have a lot of DNA in common.

DNA Changes Over Time

Ancestry tests work by tracking differences in DNA between people. They can do this because our DNA gradually changes over time.

For example, when cells copy their DNA, they don’t always do a perfect job. Mistakes called “mutations” happen and not everyone has the same mutations in their DNA.

In fact, people from the same part of the world tend to have more DNA mistakes in common than people from different places. This is because thousands of years ago, humans didn’t move around as much as we do today. What happened to DNA in one part of the world stayed in that part of the world.

This means different groups built up different sets of mutations over time.

Picture your DNA as a long book. In the old days before computers and modern technology, books were copied by hand. Monks in monasteries carefully transcribed new copies of books, but sometimes they made mistakes.

Imagine that a monk in a monastery in Poland is copying a book and makes a mistake. They then lose the original and use the copied book to make new copies. Now all the copies of that book in the Polish monastery will have that new mistake.

The same thing happens to your DNA. When there is a “mistake” or mutation in the DNA that gets passed down to a child, then that child will have that mutation. As will all of his or her kids.

Here’s the important part, though — all kinds of different mistakes can happen.

For example, getting back to our Polish monk, if he makes a mistake, that mistake will be in all of the Polish books from then on. But the Polish monk will probably make different mistakes compared to an English monk.

And a historian would be able to trace a book back to the monastery it came from by looking at the mistakes. If the book has the Polish mistake, it probably came from Poland. If it has the English mistake, it came from England.

It’s the same with DNA. People who share ancestors from the same part of the world are more likely to have the same mutations in their DNA.

And just like historians can trace where a book is from based on its mistakes, scientists can trace where you are from by looking at mutations. Since you are Eastern European, you have the same “mistakes” in your DNA as other Eastern Europeans.

So that explains why your family looks the same in this test. You all have the parts of DNA that the company classifies as “Eastern European” —those Polish-specific mistakes in that monk’s book.

Now let’s get to why this doesn’t mean you have the exact same DNA as your relatives.

A Mix of Mother and Father

Imagine our monk in Poland who copied his book with a couple of mistakes. Let’s say a bunch of monks from this monastery take a copy of the book and found new monasteries across Poland.

When they get to their new homes, they start diligently copying their manuscripts. And they each make their own monastery-specific mistakes. Now every book in Poland is no longer the same.

This is similar to what happens to our DNA, too. The people in a village in one part of Poland will have a few differences in their DNA compared to the people in a nearby village.

It is these DNA differences that “relatedness” tests will look for. And where that 50% relatedness comes from. You share around 50% of your DNA because you get half your DNA from your mother and half from your father.

So your mom has her “village”-specific differences and her “country-wide”-specific differences. Your dad has his own “village”-specific differences but shares her “country-wide”-specific differences.

The ancestry part of the test just looks at the “country”-wide differences. Which is why you look identical to your relatives in an ancestry test even though you’re not.

Your Sibling Is not an Identical Twin

So you almost certainly got a different DNA breakdown from your siblings. This would show up on a test that looks at other parts of your DNA.

In fact, this is the DNA a test like Ancestry.com looks at to find people related to you! They use those “village”-specific differences.

This becomes more obvious if you get a test from a company like 23andMe that shows which bits of DNA two related people share. Or if you put your raw data from Ancestry.com through a service like GEDmatch.

When you put your DNA through GEDmatch, you’ll see that you don’t have the exact same DNA as your sibling. This is even though you both are 100% Eastern European.

Author: Fiona Tamburini

When this answer was published in 2016, Fiona was a Ph.D. candidate in the Department of Genetics, studying genetic interactions between humans and microbes in Ami Bhatt’s laboratory. She wrote this answer while participating in the Stanford at The Tech program.

Skip Navigation

Skip Navigation